QR codes are for suckers - it's time to break them for good

QR codes are the Russian roulette of getting where you need to go online, and scanning one is the equivalent of plunging your hand into a lucky dip jar and hoping it doesn't come out with a venomous snake attached.

Take the image above for example. One of the QR codes is for this very page, another is for this writer's social media profile, a third is for a mystery YouTube video. Which is which, and how do you know?

You've got to ask yourself one question: "Do I feel lucky?" Well, do ya, punk?”

Depending on how your phone is set up, it may automatically launch the link in your browser, or it might - in a very character-limited space, give you a part of the full URL. Want to take the gamble? We don't either.

QR (Quick Response) codes are everywhere, and they're a black bag. You get a square of squares on a plain background, and that's it. They're great if you want a simple way of sharing your contact details, or giving guests access to your Wi-Fi network, but beyond that, they're a grab bag of Bertie Bott's Every Flavour Beans.

Will you get the delicious marmalade-flavoured URL you were hoping for, or the tangy faeces-tinged Goatse image you thought you'd long-since cleansed from your mind with bleach and aromatherapy? It's a risk.

Most responsible parties will take the time to copy and paste a written URL next to their QR code, so that if you, like us, are averse to blindly opening links, you can type it in, or use your favourite search engine.

But recently, we've come across dozens of unaccompanied QR codes. It's not obvious where they link to, and we're averse to trying them out.

QR novelty has worn off

There's a certain type of person, who latches on to latest technology and won't ever let go - even when that technology is now approaching its 30th birthday. In their minds, it's new and it's cool, it's the future, and should be included with everything. Remember Business card CDs? It's a bit like that.

These are the kind of people who advocate moving their corporate headquarters into the metaverse, won't shut up about NFTs, and try to persuade you to convert all your material assets to FTX-managed crypto assets.

In most cases, a QR code adds complexity, along with the need for specialist equipment. Why keep it simple, when you can add three more steps and an element of danger to the process?

We're going to give you two examples of recent encounters with QR codes and why - when they're not accompanied by written URLs - they suck so very, very, hard.

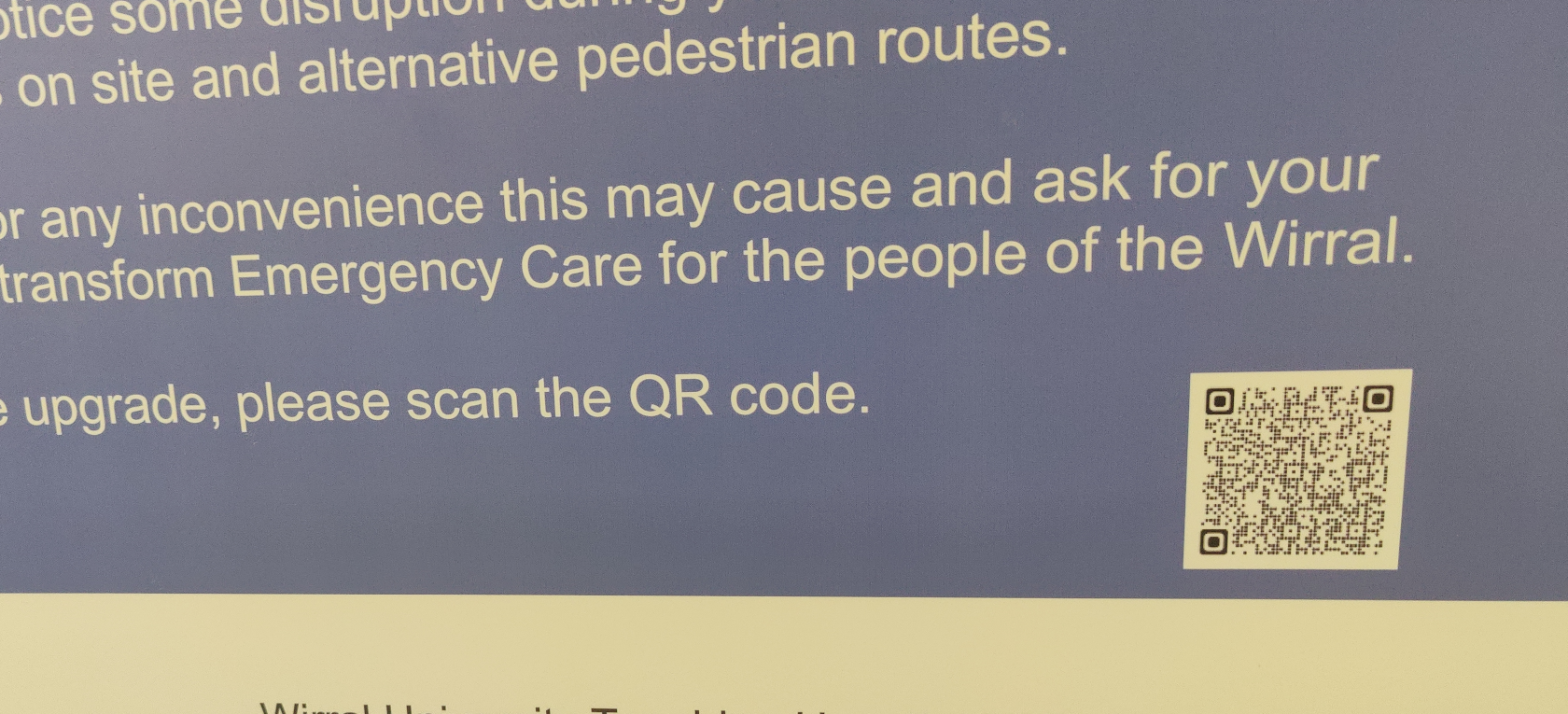

The first example comes from a trip this writer took to his local mega-hospital in April 2023. There were renovations in progress resulting in changed layouts and routes around the 15 acre site.

There were a multitude of signs explaining the basics, but if you wanted the details, you would need to scan a QR code.

The problems with this are fourfold: The first is that to scan the QR code, this writer would have needed to stand crotch-to-face in front of a benchful of exhausted patients and whip out his phone.

The second is that hospital walls do not allow mobile phone signals to pass through.

The third is that even in 2023, many people do not actually have mobile phones with QR scanning functionality.

The fourth is that there's no guarantee some local joker hadn't slapped a sticker with a malicious URL on top of the printed version.

All of these problems would be eliminated by a simple URL written longhand. It could be read from across the room, scrawled down on the back of an envelope, and used later - either with a computer, or in an area with better reception.

It would be immediately obvious if it was a legit NHS domain or something more malevolent.

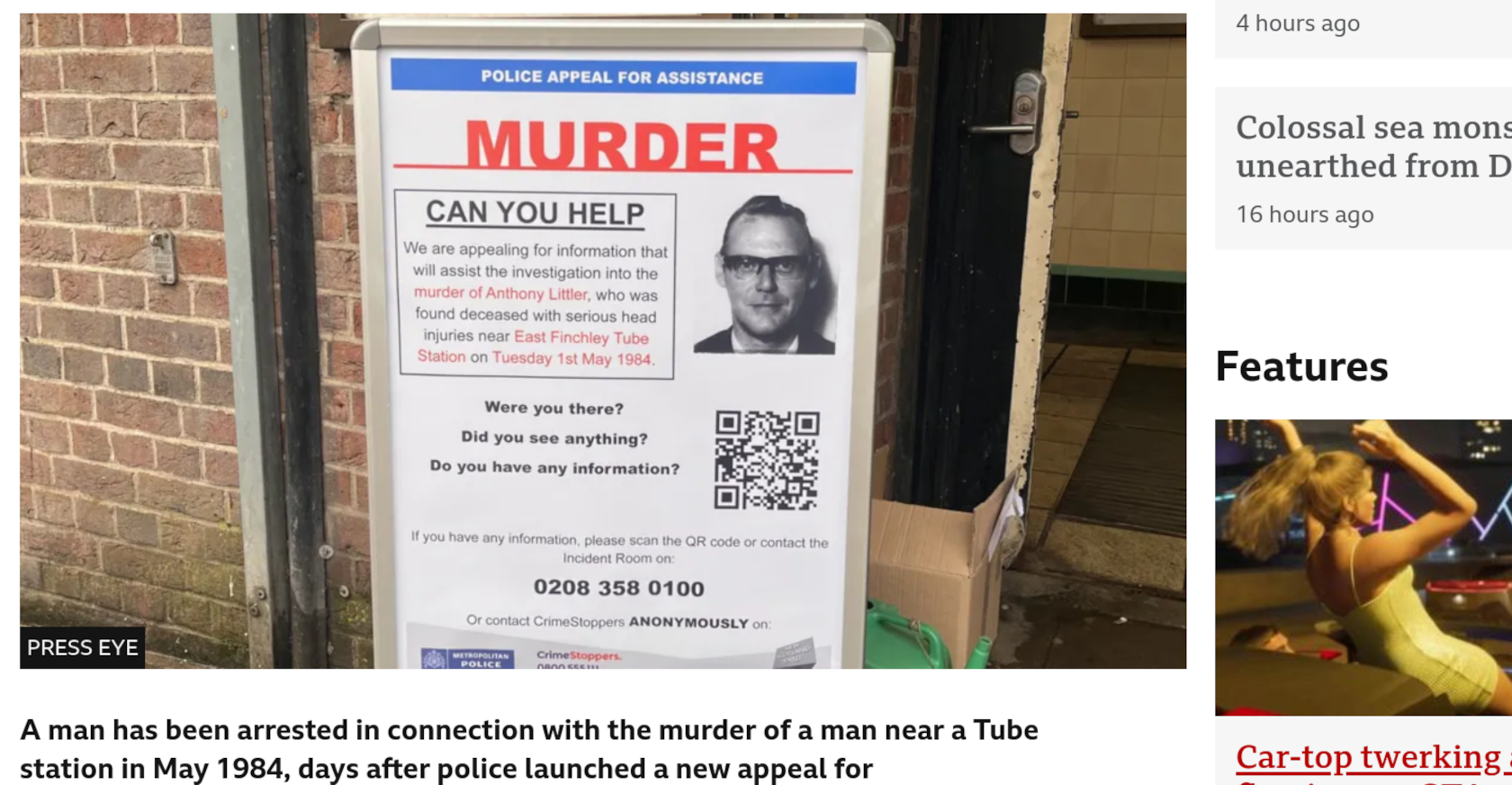

The next example comes from a BBC news story about a police appeal for witnesses to a 40-year old murder.

If you witnessed a murder four decades ago and have kept quiet thus far, it's probable that you want to remain anonymous. Contacting the police directly might lead to all sorts of unfortunate consequences - such as the need to give a statement in a police station, or appear in court and point the accusing finger.

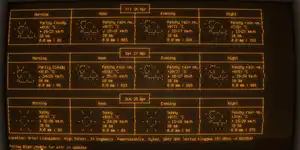

As you can see in the above image, there are several ways to give your information. You can call the police incident room directly, or you can call CrimeStoppers anonymously.

So, to which of these services will the QR code take you?

Psych! It doesn't take you to either. That QR code leads you to a particular page on mipp.police.uk - the UK Police Major Incident Public Reporting Site - it's not CrimeStoppers, and it's not necessarily anonymous. OK, the poster doesn't say that it is, but it's not immediately obvious either.

Is it confidential? would you take the chance?

It doesn't seem that there are any tracking scripts when viewing the page source - but there's a decent amount of Javascript, so we can't be sure - and text elsewhere on the site indicates that access logs are retained.

By opening that link in your browser, you're connecting to a piece of police digital infrastructure, and there will be a record that can connect it to you.

Of course, there is a brief privacy policy that states, "UK Police Forces who are committed to protecting the privacy and anonymity of anyone who contacts us with information about crime", but it goes on to say that "This statement is made in light of the requirements of the Data Protection Act 2018". A quick scan of the relevant regulation, reveals that there are various get-outs when applied to "the apprehension or prosecution of offenders". So there's that.

If we want to indulge our fancy further, we can imagine that a legitimate QR code has been replaced by a villain in an effort to entrap would-be snitches. Or that a desperate would-be YouTube star has embedded a link to his muscle car channel, or it's an affiliate link to an illegal dog-breeding ring, or a scam site that will offer a reward then empty your bank account.

Of course, you won't know until you scan the code.

QR codes are already broken

As we were writing this article, we came across a recent warning from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) warning of the dangers of QR codes.

In it the commission warns that scammers use QR codes to " take you to a spoofed site that looks real but isn’t", and that they could, "could install malware that steals your information before you realize it".

A subsequent article by the New York Times (paywall link) states that Trellix, a cybersecurity company, saw more than 60,000 samples of QR code attacks in the third quarter of 2023.

The FTC's advice is as sage and as useful as you'd expect.

Inspect the URL for "misspellings or a switched letter".

Great idea - but QR code scanners aren't really set up to provide a legible URL, and it kind of defeats the point of using them.

Don’t scan a QR code in an email or text message you weren’t expecting — especially if it urges you to act immediately. If you think the message is legitimate, use a phone number or website you know is real to contact the company.

So... don't use QR codes then?

Protect your phone and accounts. Update your phone's OS to protect against hackers and protect your online accounts with strong passwords and multi-factor authentication.

Again, this is sound advice as far as it goes, but shifts the blame to the user instead of to the poor design choices that allow this type of attack to succeed.

A broken system can break further and faster

We'd say it's a mistake to assume that most people want a technological solution to the intellectually confounding task of tapping in or writing down a URL, but evidence seems to suggest otherwise.

People want to be able to point their phone and have it open a link. But there are ways of doing that that don't require obscuring a URL behind a machine-readable square.

If companies and individuals choose not to go with simple, common-sense URL structures, the least they can do is to print a URL clearly enough that humans can read it, and the OCR app on your phone can read it too. That way, users can easily check the validity of a link, they can write it down for later, and they can have their phone do its magic.

That's not going to happen anytime soon though - despite warnings from the FTC, and the hundreds of thousands of people who fall for QR based scams every year.

The ideal solution would be for people to stop trusting QR codes altogether. It's inevitable, but it would be great if that state of affairs could be hurried along a little, and if every scanned QR code was a coin toss of unimaginable horror.

Be part of the solution

Sometimes, the only way to make a situation better is to make it worse.

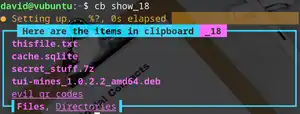

qrencode is a simple utility that does exactly what it says on the tin: it turns data into QR codes that you can print off, send to people, stick to lamposts, or anything else you want to do with it.

It's available in most of the default repositories, so if you're on a Debian-based system you can simply pop a terminal and enter:

sudo apt install qrencodeAlternatively, releases and compilation instructions are available on the qrencode project page.

We're not suggesting you do anything in particular with it, but we're not suggesting you don't, either.